Becoming an Airline Pilot...by an Airline Pilot

In an ideal world, the job you perform, is the job of your dreams, but the job of your dreams may frequently end up being...well, just a dream. The reality of becoming a pilot is not a case of "Grow up. Grow wings, Fly!", in fact, there are many hoops you must jump through, hurdles to overcome and of course, exams you will need to pass before you can actually introduce yourself as "John Smith, airline pilot and all-round hero!".

Who better to tell us about these stages and give us a real insight into what it takes to become an airline pilot than an actual pilot? Here's what he had to say:

Firstly, congratulations on becoming an airline pilot. Can you tell us when you realised that this was the path you wanted to take? When was your first dream of flying?

The first time I flew was in a glider. I hadn't flown anything before. The highest I had been before then, was 100 feet above the ground on a firefighter's ladder. I was supposed to follow in my family's footsteps and become a firefighter. Someone had told me that flying a glider was good fun so I decided to give it a go. Before giving it a try, I had a few second thoughts but the moment I actually took my first flight I felt: "OK - now I know exactly what I want to do in life"!

Describe that feeling when you were actually up in the air.

It was a shock! The whole flight only took about five minutes, but it was amazing to be up in the air and see everything below. Also, gliders are practically silent so the whole experience was both magical and peaceful. I felt a kind of oneness with the glider, which probably sounds funny to anyone who hasn't tried it, but honestly, you start to feel like a bird.

How old were you at the time?

I was seventeen.

Had you dreamt of these things when you were a kid?

Not really, no. Honestly, I wouldn't have discovered the wonders of flying if I hadn't actually tried it. I would have probably ended up fighting fires instead!

If I too wanted to become an airline pilot, what single piece of advice would you give me? What kind of characteristics or features do you think I would need?

Go for it! I think the most important thing that a pilot needs is resilience. Resilience builds everything else. If you fail sometimes but can move on, that's great. Sometimes you might forget something, you might make some minor mistakes, but if you can accept them, move on. Don't dwell on your mistakes, but focus on your airplane which is in constant motion. That's why resilience and the ability to avoid dwelling on your mistakes is a really important characteristic.

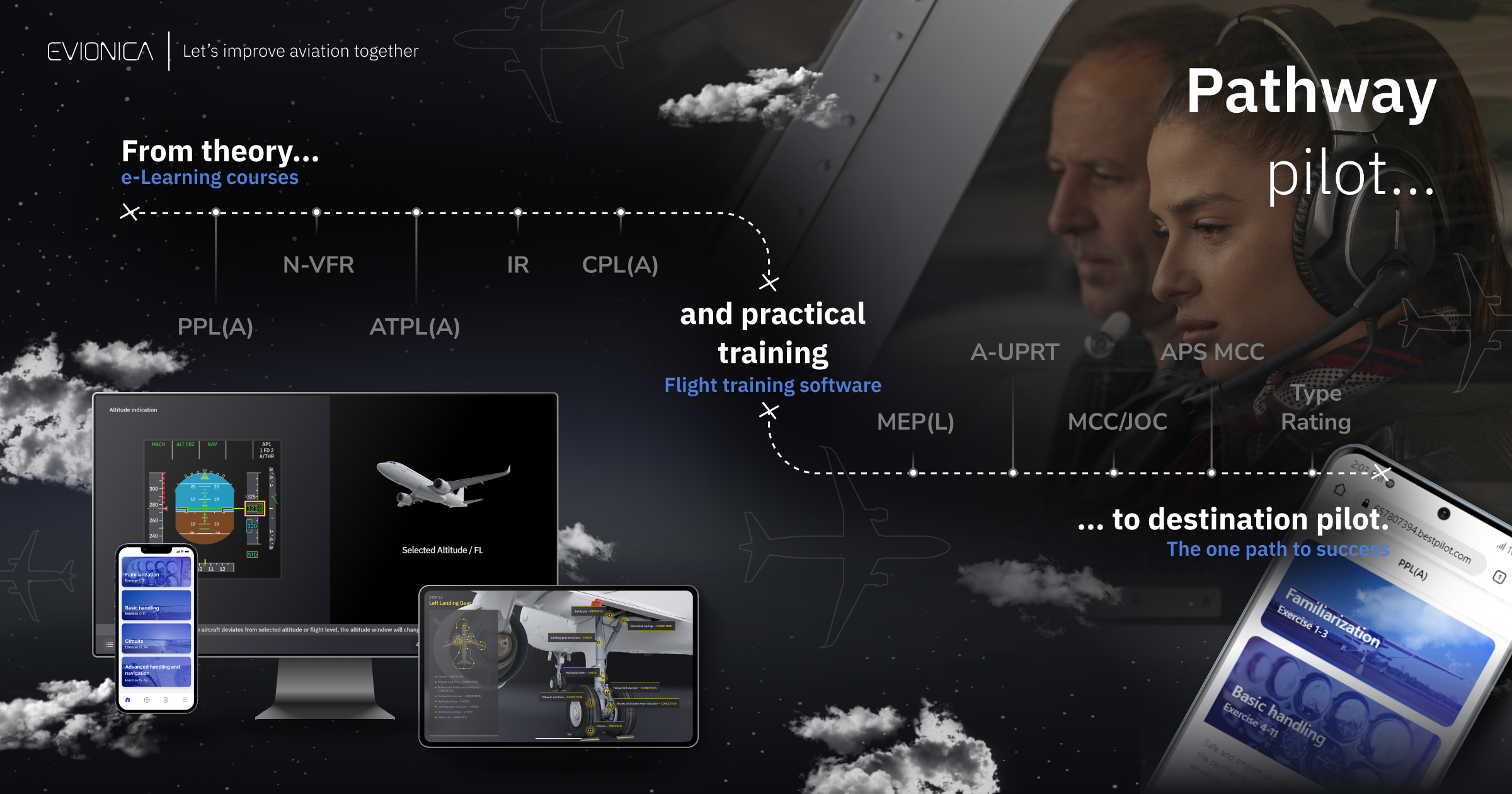

OK, so let's say I've got a dream to become a pilot. I have no idea which kind yet, but what are the first things I must do? Tell us about the stages to actually become an airline pilot.

In Poland we have - I think - five different universities that offer government sponsored flight school training. For me, it was just a case of applying to one of the universities that offered these programs. In my case I ended up in a city called Chelm. I knew that the first thing I would need was the Private Pilot License (PPL) so after I finished high school I went to Germany, saved some money working there delivering mail, and got enough money saved for the PPL license. I then went to the university to start my course.

Someone had once told me that if you want to be accepted into the actual pilot program rather than another course, you really need to put the hours in during your first year so I worked really hard throughout that year. At the beginning it was quite daunting, looking up at all the people flying and me thinking 'oh, I haven't even touched the airplane yet'. But I just worked my way through, and focused on the things I could do. Thanks to that attitude, I managed to achieve my goal and got on the actual pilot program.

I guess that comes back to the resilience you were talking about.

Exactly. All of my focus was on studying so I managed to qualify for the pilot program. The actual flight training started from the second year. Even when others decided to go away on vacation, I stuck around - I was the guy who was still up in the air flying.

I suppose not everyone got accepted on the program. Why do you think you were chosen?

I think it might have been clear to some people, including the interviewers, that that I had done everything humanly possible to get onto the program. I had really applied myself and they could probably see I had an extremely high level of motivation.

%201.png?width=1520&height=606&name=Group%201260822031%20(1)%201.png)

Well, one of the things that gets talked about a lot in aviation is decisiveness. I suppose with your motivation and sense of purpose, maybe they saw that trait in you.

Exactly. Also, one of the demands that the university had was that you must be available to fly. No matter whether it's your vacation or not, making yourself available is essential. I was fine with that as I wasn't particularly interested in posing in front of an airplane to post pictures of myself on Instagram. I was determined to do anything it would take to become what I wanted to be. I suppose that determination came across in the interviews as well as in the assessments.

So let's go through the actual stages. You start with the PPL, how many questions do you get asked there?

Hmm, I think two to three thousand right now but it's such a long time ago that it's hard to remember. You need to get 75% in each exam part - that's what you require no matter where you choose to sit the exam.

What comes next after the PPL? I guess it's the NVFR.

That's basically how the first part looks and then you do the NVFR with your instructor - a few takeoffs and landings during the night which is the first step after you've got the PPL license.

Do you have any exams during the NVFR course?

You need to take the theory class, there's no CAA exam, just an internal exam in the flight school. Then, you do the flight training but without any CAA exam as it's a "night rating" course, not a course that gives you a separate license.

OK. So, you've done the PPL, moved on to the NVFR night rating course and what next?

OK. So after you've done the Instrument Rating course, you've got your MEP(L) course I guess?

Yes, at this stage you learn how to fly with more engines. It's still an aircraft but when you're dealing with more engines there are certain aerodynamic changes - the forces are different, the aircraft is more complex, their operating speeds are faster, your reactions must be different and so on. Because of all these additional challenges, MEP(L) comes later on in the training.

Right. What comes after that? I've done a bit of research and I see that there's something called the A-UPRT, what's that all about? I

t stands for Advanced Upset Recovery Training. An "Upset" is an undesired aircraft position. Here's an example: if you're approaching stall because you are flying too steeply and your speed is dropping and as a result, you're heading to the ocean, that's an example of an upset. A lot of courses were introduced because of catastrophes caused by inappropriate pilot action. This course is one such course. There was a catastrophe because the pilots had lost altitude as the indications were not reliable and the aircraft entered a stall. Instead of applying the recovery technique, the pilots kept pulling the stick which made the situation worse and ended up causing the aircraft to crash into the ocean. This course is therefore essential if you want to become an airline pilot.

The next course along the line seems to be the Multi-Crew Cooperation (MCC) and Jet Orientation Course (JOC). Are they theory plus practice?

Yes. By now you are really good. You've done 150-200 hours of flight time, your expertise is getting better and better, you're more comfortable and capable, but... on the actual job, you're with another person, you're not alone anymore. You need to share your tasks with them. You're both performing vital roles and you cannot think that one is more important than the other, everyone's role is vital.

CRM sounds a bit strange to me. Is it really possible to train someone who isn't assertive on how to become assertive?

It's definitely possible as I myself wasn't a particularly assertive person. When I was doing my MCC training, I started practising assertiveness in my day-to-day life.

I'm curious who you practised on!

Well, there was some advice I received, that "if you are worried about speaking out about something, just speak out". Now, I don't feel so shy about speaking out about things. Of course, sometimes in life you just let things go, but from my own experience, it is definitely a skill that can be trained.

What about the Jet Orientation Course (JOC)? How much of a surprise were the things you learned on the JOC course compared to what you'd learned before?

It's hard to put my finger on one thing in particular that was an "epiphany" or a "game-changer", on this course, but the fact is - if things start going badly in a Jet Aircraft, they can really start going wrong. The margin for error on a jet aircraft is very, very small so you really need to step up your game.

_LMS%201.png?width=500&height=334&name=Jet%20Orientation%20Course%20(JOC)_LMS%201.png)

One thing that baffles me is that from a non-flier's perspective, there are many things you learn that seem to be irrelevant. For example, some of the early courses seem to talk a lot about clouds. If I was a learner, I'd get fed up spending so much time learning about clouds. Do you really need to know your cumulonimbus from all these other different cloud types?

Yes, yes, yes! Meteorology is a very important thing in aviation. Once you understand these things, you will know a cloud just by looking at it. Let's take cumulonimbus as an example. Believe me, when you're flying, you don't want to get anywhere near a cumulonimbus cloud because it's nasty. Passengers can get injured, even fatally injured, the aircraft can get badly damaged, so many bad things can happen.

That's interesting. When you're doing a lot of these theory courses, is it made clear to you how all the theory is connected to, for example, flight safety?

Yes, I believe it is. If you know your meteorology, you will be able to make connections immediately and paint a picture of the situation you find yourself in. That's what we're trained to do - to make connections between what we are experiencing and what we have learned. Once you actually start your job, you can make connections with all the theory quite easily.

It might sound a bit robotic, but personally, I had felt there was a massive knowledge gap that this course filled. Once you had done all your training, gone through the interview, done the type rating - which in itself was very difficult - and then finally arrived at the "line" I noticed that "on the line" there were so many things I still needed to understand. There was so much unwritten knowledge where there are so many tricks you wouldn't have picked up on without this line training. For example, in this training someone tells you to "Get on the headset". Normally, you probably wouldn't know what they mean as you could interpret it in a million different ways. In this training, you learn all these little things and all the actions you need to take. These are things that have a real effect on your day-to-day job. On top of that, you get trained on all the flows in the aircraft, what to do in particular scenarios. That way, you fill so many knowledge gaps by doing this course.

Well, you can either do it yourself if you have the money for it, though it can be quite expensive or it can also be sponsored by the company if you get the job. Some of the companies offer sponsored type-rating courses for you. They pay for the training and deduct a certain amount from your salary.

Yes. If you get a job with an operator that flies different aircraft types, for example Boeing, Embraer, Airbus, in this case, once you've been accepted in the job interview, you will be notified which type rating course you will get.

And that's theory as well as practice?

Basically, once you've built up your hours, you're more attractive to an airline. The first job is often a case of grabbing the hours, getting the experience and after some time, your position in the market will start to improve very fast and you'll see plenty of offers rolling in. Let's take a Ryanair pilot as an example. Let's say they're Boeing type-rated. If this pilot were to go to Emirates, they could receive an offer for an upgrade to the Boeing 777, which is also Boeing, but a bigger type than that flown by Ryanair.

Wojtek B. Graduation day for a soon-to-become airline pilot.

Wojtek B. Graduation day for a soon-to-become airline pilot.From zero to ATPL, if you do it privately and pay for it yourself, you can do it all in about two years.

No - if you're talking about flying a small piston aircraft, you can do that in about two months, maybe even one month if you're fast as you only need the PPL.

Yes, it's two or three comfortable months. You can still do your regular job and your training at your leisure.

On average I'd say that's about right.

It's about two years. From the moment you first say "Hey! I have no idea what a plane is," to when you can finally say "Hey - I'm an airline pilot!".

It all depends on the flight school. You can complete the pathway on different aircraft, do more hours, but it all depends on the school, the aircraft, all of these factors.

Thank you Wojtek for sharing your insight with us and we'll share some more of your experiences with our readers very soon.

_LMS%201.png?width=500&height=334&name=Night%20Visual%20Flight%20Rules%20(NVFR)_LMS%201.png)

%20(MEP(L))_LMS%201.png?width=500&height=334&name=Multi-Engine%20Piston%20(Land)%20(MEP(L))_LMS%201.png)